User Experience is full of surprises. Each challenge is unique, necessitating a distinct approach. A good User Experience (UX) achieves the software's goal and meets the user's expectations.

Recently, I was invited to speak about user interfaces and user experience at the Future Trends in Nuclear Physics Computing workshop at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (JLab) in Newport News, Virginia (program information available here). I was pretty excited, as I am a bit of a science nerd, and I was interested in seeing what kind of unique UX & UI challenges these scientists face and how I could help.

Is Good UX/UI even needed?

There’s no checkered flag when a piece of software achieves “good UX” – it’s an ongoing process of iterative improvements driven by data and insights. However, you can gauge the quality of an application’s UX by simply working with the software – good UX is usually completely transparent. Most times, we notice bad UX because it is frustrating or doesn’t work the way we think it will. Bad UX can result in people not using software, or, in some circumstances, can even be dangerous.

One JLab scientist brought up a good point, mentioning that the users of most of the software are scientists who are accustomed to command-line interfaces. In this case, is a good visual UI needed at all? The answer to that question could very well be ‘no.’

Sometimes it’s all about the initial question. If, when we went to the moon, we asked, “Is there a reason to go to the Moon?” the answer may very well have been ‘no’ as well. But what if we approach this question a little differently, such as ‘How would good UI affect our scientific process?’ We might get different answers. Here are just a few ideas illustrating how changing the question can alter the experience, and how effective UI can significantly impact the scientific process.

Scientists also have to apply for grants by showing how their results could impact the world or the scientific community. Many people who will present their experiments during this application process aren’t part of the scientific community. A well-designed User Interface can enhance the understanding of the experiment and make the information more accessible to those outside the scientific community.

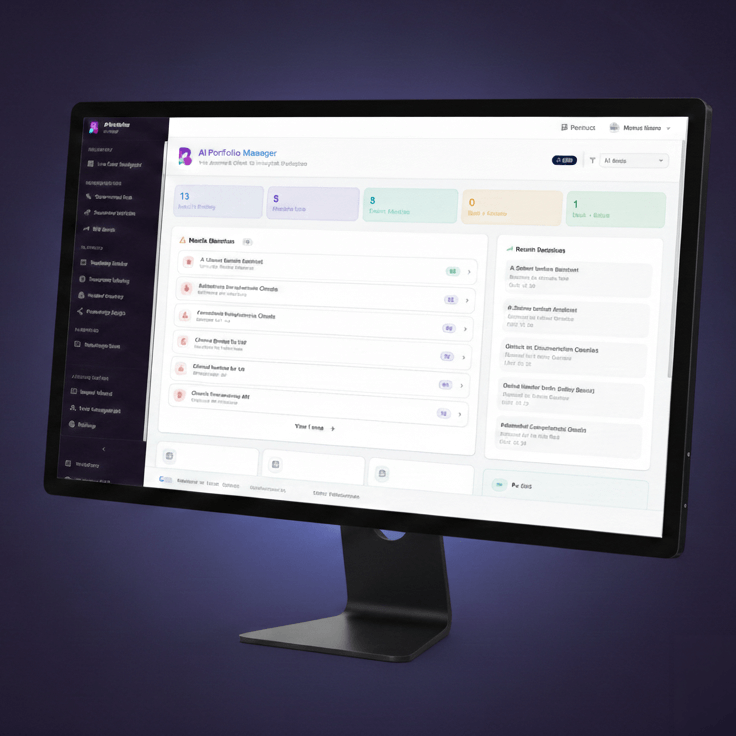

My job as a UX/UI Designer is not only to design better software, but also to present it in a way that is understandable and engaging to project stakeholders. This means I’m not always presenting UI directly to the user. In most cases, I must present to clients and stakeholders who often lack a thorough understanding of every use case. Usually, they come to the table with their agendas, based on business objectives for a piece of software, without fully understanding the software from the user’s perspective. In these instances, it’s vital to present a UI that clearly shows how the software fulfills the user’s needs and, in so doing, accomplishes the business objectives. This is where our role as UX/UI designers becomes crucial and empowering.

It can be challenging for those outside the scientific community to comprehend the intricate inner workings of scientific experiments. Yet, communicating the details of these experiments and the value they bring to stakeholders within the complex infrastructure of governments and universities is what allows scientist to continue their work. This makes creating a simplified User Interface to present experimental data even more critical.

UX/UI 101

One of the workshop's requests was to present a “User Interface 101.” The organizer said ‘Most people in this community are used to command-line interfaces and have no idea how to group information and design a GUI that focuses on the user and not the program.’

Given this request and not knowing the specific challenges they faced, I wanted to plant some seeds in what I’ve generally found makes good UX/UI. A lot of UX is about the approach, asking the right questions, and opening your eyes to how people are using the software, rather than making assumptions. You can read through my presentation deck here.

There were many questions during the Q&A portion of my presentation. Luckily, I had the last slot of the day, and there was an allotment of discussion that followed, so quite a few people asked questions and sparked some great conversation.

A Typical Scientific Procedure

I learned a great deal about the process these scientists go through for their experiments. I’m sure it gets way more complex than this, but let me summarize the method based on my observations:

- First, they must come up with an experiment that will test out a hypothesis or otherwise bring value to the scientific community.

- They must ensure they can modify the particle accelerator so that the experiment can use it safely and be able to monitor results.

- Get approval for a grant or other funding.

- Design a user interface to make sure the experiment is going as planned. While the experiment is running, it can operate continuously for weeks until it is complete. There may be shifts of personnel to monitor the data coming in 24/7 and look for problems in case the experiment needs to be shut down.

- After the experiment is over, there is a vast data set that they must find somewhere to process and interpret the results, many times with a user interface or other graphics.

From what I gathered, they essentially have to design two types of UI: one for running the experiment and one for interpreting the data results.

The Challenges the Scientific Community Faces

In the scientific community, where governments and universities typically provide funds, and money is often limited, scientists must undertake a wide range of complex tasks, and there is limited funding for dedicated resources or specialized expertise. Many of the scientists I spoke with are also coders and code most of their experiments themselves in Java or other languages. It’s remarkable how many tasks they face, and it's essential for us to understand and empathize with their unique challenges.

In some ways, this is not unlike my own experience as a UX/UI Designer. In a full-blown, consumer-facing app, a UX/UI Designer might work with other disciplines and spend weeks crafting a superior User Experience. With smaller projects and budgets, there’s less time available for design or UX, and many may conduct little to no user testing or QA (quality assurance). As a UX/UI Designer, I’m constantly challenged by how to create better software within a limited budget or timeframe. Below is a list of possible solutions that even non-designers with little UX experience can use to craft a better User Experience.

Solutions

1. Define the User

One particular area that goes a long way in software design is defining the User using user personas and user stories. Essentially, our goal is to determine who will be using the software and the specific situation they will be in. User stories help define why the person is using the software, which helps bring out key elements (#2 on this list). At a basic level, it doesn’t take much time, but better software usually takes into account all the different types of users and edge cases.

2. Prioritize key elements & rank importance

Before building software, it’s good to come up with a detailed list of what the software is supposed to achieve. Sometimes software is confusing or complicated to use because it tries to do too much and doesn’t do any one thing well. Rank the software's features in order of importance. Sometimes this helps eliminate features that could be added later or removed, ensuring that the most critical and frequently worked-on features have the most significant impact. Doing this before you start on any User Interface design can be helpful because you’re thinking about features from a top-level perspective, rather than how they look, thereby separating function from form.

3. Use resources around you to conduct usability testing

Sometimes colleagues, friends, and family are incredibly valuable resources. I constantly show my work to people who haven’t seen what I’m working on to get their thoughts. This allows me to get an opinion that is less biased than that of someone who has already seen it. Conducting usability testing with people around you can provide valuable insights into the User Experience of the software you design. Often, they will give you insights into obvious things that were somehow overlooked. Or they may add a small idea that has a significant impact. I can’t tell you the number of good ideas I’ve generated from showing people and incorporating their opinions.

You can test people with drawings, mockups, or complete software. Try not to guide them, but ask them to complete a task and sit behind them to see what they do. You might consider asking them to verbalize what they are thinking. This is fundamental user testing anyone can do, and in my experience, the insights are always unexpected and highly valuable.

4. Leverage knowledge and online resources

The stacking of technologies is what makes the pace of technological advancements so rapid. We are in the era of software creating software. A designer uses software to design software. If designers had to start from scratch, we wouldn’t have any time to develop and enhance the look and feel of the software we create.

Designers have created a community to share resources for the platforms we design for. We have magazines and blog articles. We have created UI kits and icon kits to make things faster and more conducive to the platform, allowing us more time to focus on UX and more complex problems. Developers have done the same thing with GitHub. Front-end developers can use WordPress or a similar platform like Basecamp. Leveraging knowledge and prior work is key. Anyone developing software can find free icon kits and code to reuse from numerous resources.

During the questions, I suggested that the scientific community do the same. If one scientist has built an interface, reuse it if possible. Share knowledge. Build upon what other people have done, what works. It was great to see that a few people in the room had already leveraged these resources to increase the impact of their UI.

Spreading the Knowledge of Good User Experience

It was a fantastic opportunity to learn about the current challenges faced by scientists from institutions like NASA, MIT, JLab, & Fermi Labs, and how they are learning to overcome them. I trust that my presentation, talk, and this blog article can help spread good user experiences and encourage a multifaceted approach to improving software for the people who use it.

Links:

Future Trends in Nuclear Physics Computing

March 16-18, 2016

Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility

Newport News, VA